Sales Pitch: Every smoker’s been there. We try cutting cold-turkey; we switch from cigarettes to Nicorette. But before the thought’s even put to words, our brains and our bodies miss them – our fingers tips twitch. A day, a week, a month later, we tell ourselves we just can’t hack it, and find our yearning fingers once again pointing to the shelf behind the cash at the nearest gas station to ask for a new pack.

Now, the decision’s no longer up to you! Retrain your automatic response to cigarettes with the coughing box! Each time you reach for a cig, you’ll hear your future in wheezes and sputtered coughs – each hack asking you, “Is this really what you need?”

“We both used to smoke and he was always trying to quit,” David Mogil, a former employee of the Coughing Cigarette Box said about his boss in a memorial post on an online obituary. “But it seemed the only thing he was quitting was buying cigarettes, not smoking them, because he was just smoking mine.”

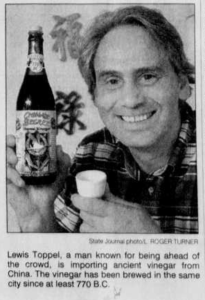

Lewis Toppel, of Wisconsin, died in 2009 and was remembered fondly by Mogil as a mentor and a shrewd man of business. A realtor, a clothing store owner and a Chinese vinegar importer, the man who helped popularize painters pants in Madison in the 1970s could make a go out of pretty much anything he landed on.

“Toppel is one of those rare people who can recognize a great product and convince the rest of us we can’t live without it,” reporter Susan Lampert Smith wrote in a 1996 issue of the Wisconsin State Journal, for a piece on the entrepreneur’s then-latest venture, an ancient Chinese vinegar.

Like his kite store (and connected kite festival, which no doubt created demand for the store), Toppel saw his pursuits take flight, more often than not.

The fact that both actress Lily Tomlin and President Jimmy Carter both visited his clothing store (one for a pair of earmuffs, the other to avoid an unruly crowd) certainly couldn’t have hurt his publicity either. Nor the fact that he saved a town-favourite burger bar and in so doing earned himself free hamburgers for life. Toppel’s own shop, Bigsby & Kruthers, later gave way to a Hallmark greeting card store (read on for the relevance of this).

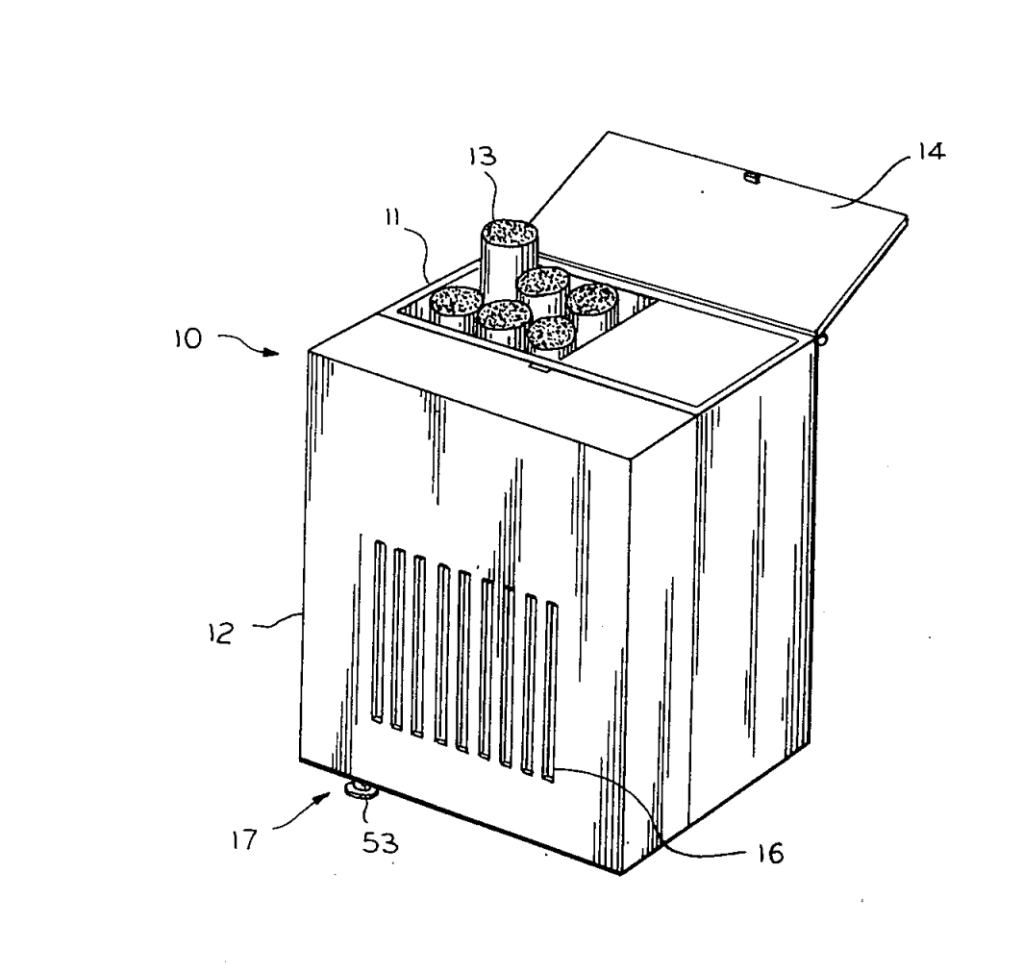

Toppel knew how to pitch a product, a knack which formed the basis for his coughing cigarette box. His device, he writes in his patent, is aimed to 1) deter people from smoking and 2) “provide a novelty device, which can be used as an advertising novelty.”

The auto-play box, he imagined, would work “to either simulate a cigarette package so that when a would-be smoker picks up the package, a loud coughing noise is emitted, or else it [could] act as a cigarette holder to actually deter a potential smoker from smoking by audibly drawing to his attention the ill effects of smoking.” A reverse-Pavlovian device, the audible trigger would, in theory, dissuade the user from picking up that which they so crave.

Modern Applications

While more than half of the world’s countries require tobacco products to be wrapped in images of blackened lungs, cancerous throats and children on respiratory devices, the U.S. currently has no such requirement for cigarette manufacturers. Beyond a sterile “SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING: Cigarette Smoke Contains Carbon Monoxide” label slapped across the top of a pack of Marlboros, the Federal Drug Administration and politicians have failed to enforce graphic health messages common elsewhere. The same four warnings have remained unaltered on American cigarette packaging since 1984.

“Research shows that today’s warnings have become virtually invisible, failing to attract much attention or leave a memorable impression” reads a release from the FDA on new proposed packaging. “Their unchanged content over decades, as well as their small size and lack of images, undermines the current warnings’ effectiveness in conveying relevant information about the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.”

The FDA has tried on several occasions to haul the U.S. into the modern world of truthful advertising on cigarettes, and, after several successful challenges by tobacco companies, may finally succeed within the next year. Companies are required to submit their new packaging designs to the oversight body by March 16, 2021, to be rolled out in 2022.

Instead of merely catching up, the FDA could consider jumping ahead with Toppel’s concept. The patent expired in 1989, but the idea itself still has legs.

Author’s Amendment

Toppel’s patent essentially covers the creation of an automatically triggered music box, like the wind-up ones of yore, which spun a bumpy cylindre to pluck measured tines and produce notes. Swap out the cylindre and tines for a mini record, and voilà.

His invention was clunky, its size a drawback to its purpose. But consider the musical Hallmark card. Not much bulkier than your average “Happy Birthday, friend!” greeting, just noisier and less recyclable.

In the 1990s, musical cards found a challenge with their price point. A 1999 New York Times explainer on how they work said that they would retail for around three times as much as a regular greeting. Today, you can send your best friend a “Crazy Chicken Musical Birthday Card with Motion” for only $8.99 US, plus postage, and you can delight at the fact that when they open it, they will be instructed to “Celebrate accordion-ly!” while they’re being serenaded with the Chicken Dance. (Do not expect an invite to their next birthday party.)

Cram that same analog chip into the opening fold of a cigarette pack and you accomplish two dissuasive goals: 1) the coughing and 2) a slightly increased price that may leave an even worse taste in the mouths of some smokers. Plus the crummy sound would presumably only enhance how grating the cough coming from a cigarette pack would be.

Leave a comment